In 1935, the physicist Erwin Schrödinger told a joke—about a cat. Leaving aside the intricate physics, the basic premise was this: a cat inside a sealed cardboard box could be imagined as both alive and dead, simultaneously—at least until someone opens the box and looks. As long as the cat remains hidden, its state remains uncertain, suspended in the imagination of the observer.

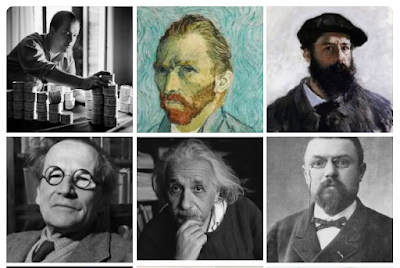

The point of the joke wasn't the cat—it was the observer. And in physics, this observer had only recently arrived. In 1905, Einstein brought the observer into physics with his theory of relativity. Until then, "the observer" was more of a philosophical figure, found in art and thought experiments. But even before Einstein, in 1898, the mathematician Henri Poincaré had started discussing the observer's role in his paper La Mesure du Temps (The Measurement of Time), where he raised foundational questions about time and its subjectivity. But what's rarely acknowledged is this: nearly forty years before Einstein, and thirty years before Poincaré's paper, the Impressionists—painters in 1860s France—had already explored these same ideas, not through mathematics or theory, but through vision, feeling, and light. They argued, implicitly and often explicitly, that reality is not a fixed, objective thing—it is experienced subjectively, shaped by time, emotion, and the eye of the beholder. A painting doesn't exist as a single truth; it comes into being only when observed. And with each observer, it transforms. A landscape at sunrise isn't the same painting to two people—or even to the same person, at different moments.

The Impressionists knew this firsthand. As they painted the world around them, they saw how light, mood and personal emotion shaped their representation of reality. And they knew that whoever looked at their paintings would re-create those realities in their minds, bound by their own time and feeling. Their paintings weren't just about the world but about experiencing it.

Yet their discoveries were never treated as theoretical breakthroughs. They were filed under artistic perspectives, not truth. The world didn't recognise Monet's "Impression, Soleil Levant" (1872) as an epistemological proposition. Instead, it waited decades for Poincaré to theorise it, Einstein to mathematise it, and Schrödinger to dramatise it—with a cat. These scientists are celebrated for "discovering" that reality is observer-bound. But the Impressionists proved it visually long before.

Poincaré was undoubtedly aware of Impressionism when he published La Mesure du Temps. Einstein, too, lived in a world shaped by these painters. And by the time Schrödinger came up with his cat, Impressionism had already passed into history. Yet, the scientists were hailed as revolutionaries—while the artists remained in their museums.

Even today, the world waits for science to confirm what art has imagined and demonstrated. While the art world has moved into newer territories of perception, imagination, and embodiment, much of science still loops around early 20th-century metaphors, often failing to expand its creative reach.

Take Vincent van Gogh—the tragic hero of Post-Impressionism. Long before he died, he had already moved beyond Impressionist questions. "I don't want to paint things as they are but as I feel them," he said. And he did. His turbulent skies, burning suns, and trembling landscapes weren't literal but emotional truths. His paintings are not representations but revelations—each one a subjective world, alive with feeling and moment. Van Gogh wasn't documenting the visible. He was transmitting interior reality.

Now imagine Schrödinger's cat not as a quirky paradox about quantum states but as an emotional metaphor. The cat is not both dead and alive because of subatomic particles—it is both dead and alive because the observer's emotions are unresolved. Reality isn't created by consciousness alone—it's shaped by longing, anxiety, fear, and love. It's not about collapsing wave functions—it's about confronting emotional truths.

In 1961, when Piero Manzoni released his infamous artwork Artist's Shit—a series of sealed tins he claimed contained his own faeces—it was widely seen as a satire of the art market. But it can also be read as a bitter critique of scientific and cultural dogma. Like Schrödinger's cat, the truth of the tin lies in belief, perception, and the unseen. Manzoni didn't just mock collectors—he mocked the entire culture that demands "proof" through empirical validation, ignoring the lived, felt, and imagined.

This is the more profound irony: a world with tunnel vision, able to recognise truth only when filtered through science, even as art keeps expanding the boundaries of what truth might mean. We are stuck, still trying to "measure" time and reality with rulers and equations—while ignoring the symphonies of meaning that have long been playing in colour, form, and sensation.

Recently, as part of my research, I had the opportunity to read a lot of books comprising nearly 90 essays on practice-based research in art, authored by academics from across the globe. Despite the diversity of voices, what struck me was the persistence of an old binary—the tired distinction between artistic perspective and scientific truth. Time and again, the essays reinforced the idea that an artwork is merely a perspective, while a scientific formula constitutes truth. Within this framework, practice-based research in art is expected to conform retroactively to structures of academic validation: art must function as a hypothesis, its process as an experiment, and its outcome as a form of proof. Yet paradoxically, the artwork itself—the very heart of the inquiry—is denied epistemological validity. What academia ultimately seeks, it seems, is not understanding but domestication: the attempt to pin down, label, and institutionalise something inherently elusive. It's like trying to tame a butterfly and call the cage its natural home.

No comments:

Post a Comment